Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Institute for Mental and Organisational Health, FHNW

06 June, 2025

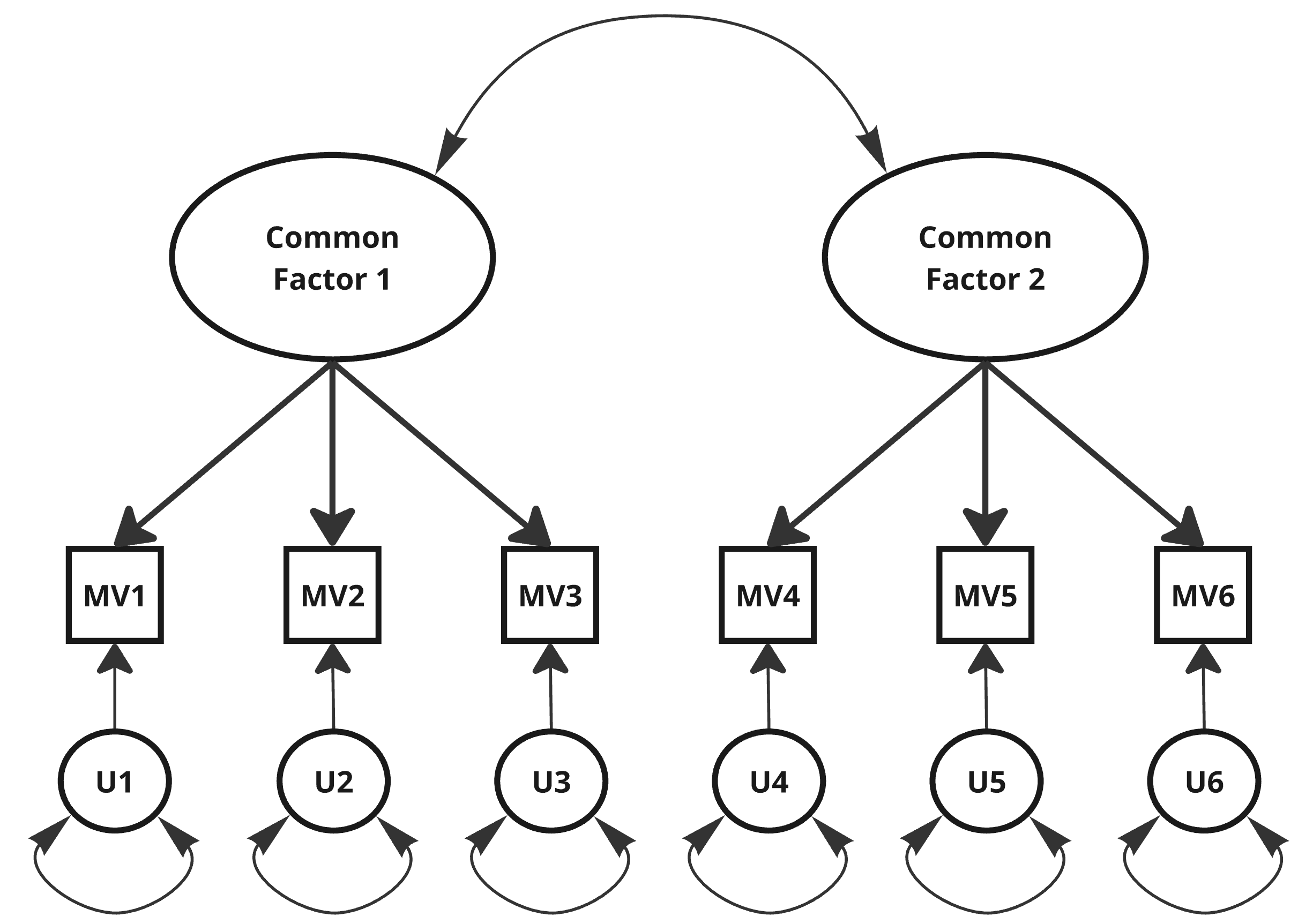

CFA

- Each indicator is allocated to a factor, other loadings fixed to 0 \(\rightarrow\) achieves simple structure; no rotation necessary.

- Loadings can be fixed to specific values or constrained to equality.

- Uniquenesses can be correlated (e.g. to account for wording effects).

- More parsimonious than EFA due to fixed parameters.

When to use CFA

- Scale construction

- Reliability

- Construct validity (discriminant and convergent)

- Method bias (MTMM)

- Scoring

- Test for a general factor

- Testing measurement models in SEM

- Model measurement error

- Test measurement invariance

Specifying a Factor Model – Path Diagram

Specifying a Factor Model – {lavaan}

{lavaan}-Syntax:=~denotes a latent variable measured by indicators.- By default, covariances between CFs are free.

- Fit the model with

lavaan::cfa()(you can also uselavaan::sem()). - Obtain Output with

summary()

Scaling the Latent Variable

- A latent variable is unobserved and must have its scale identified.

- Usually, one of two ways:

- Marker or reference indicator.

- Most popular method and default in

{lavaan}(first MV per CF). - Provides an unstandardized solution.

- Most popular method and default in

- Fixing the variance to a specific value, usually 1.

- Provides a partially standardized solution.

- Marker or reference indicator.

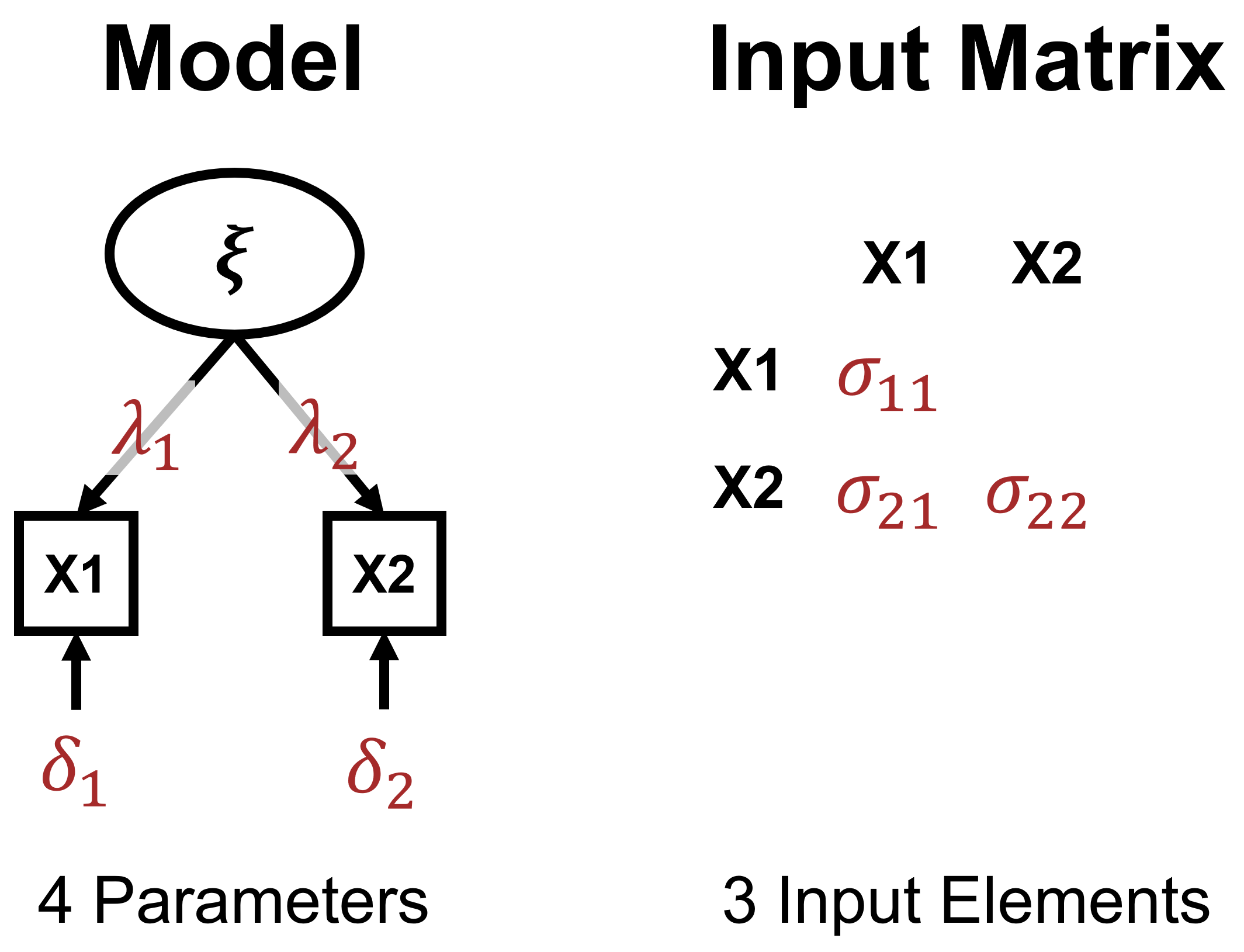

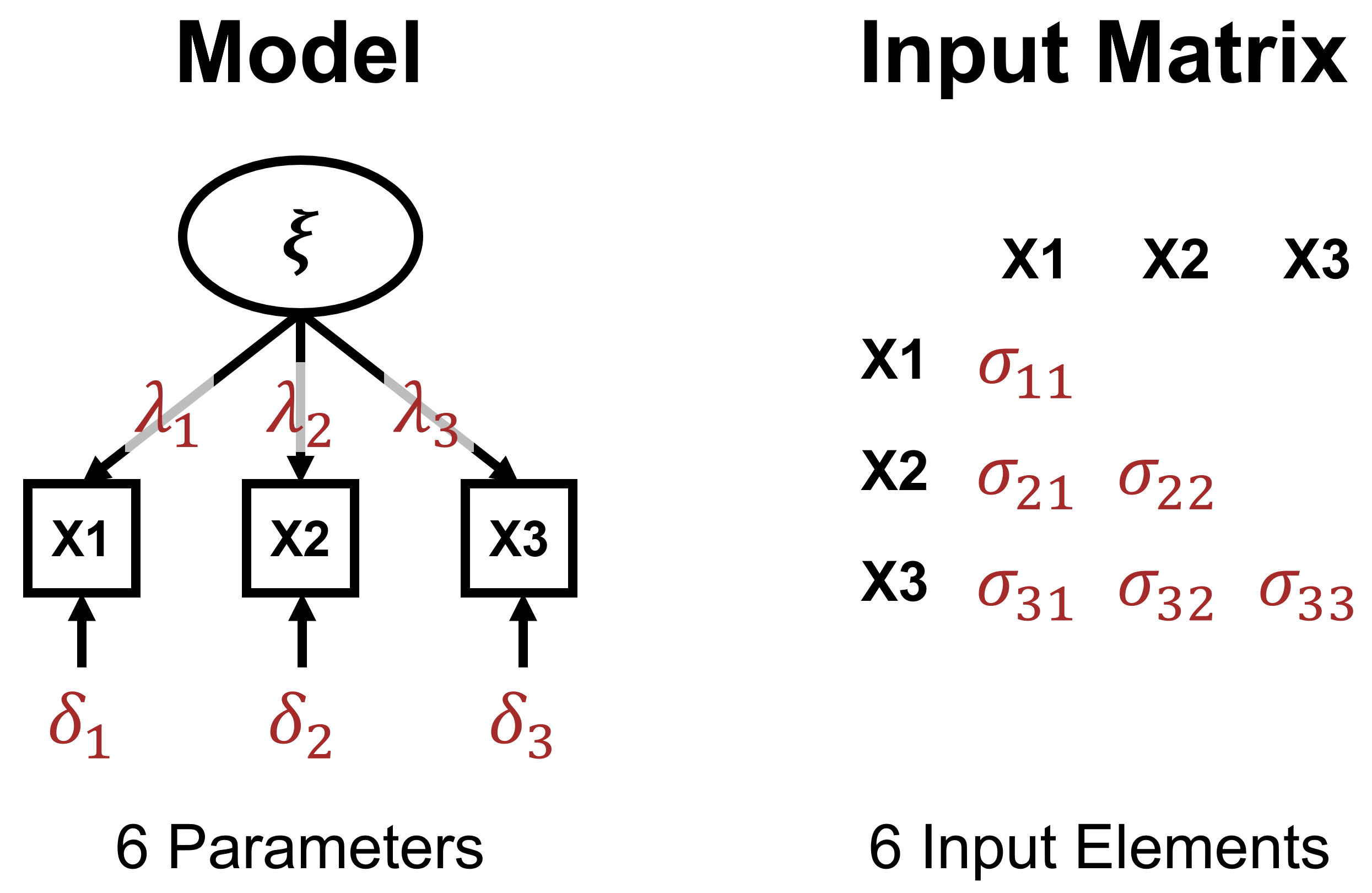

Model Identification - I

- Based on difference between information in input matrix and freely estimated parameters.

- Three possibilities:

- Underidentified model \(\rightarrow\) More unknown than known values (negative \(df\)s).

- Just-identified model \(\rightarrow\) Equal number of unknown and known values (0 \(df\)s).

- Overidentified model \(\rightarrow\) Fewer unknown than known values (positive \(df\)s).

- Number of input elements with \(p\) MVs: \(p(p+1)/2\)

Underidentification

Just-Identification

Overidentification

Model Identification - II

- CFs must be scaled

- # input elements \(\geq\) # freely estimated model parameters

- Overidentification with two or more MVs per CF from two factors on, but min three MVs per CF should be used to avoid empirical underidentification

Model Estimation

When using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation, parameters are found by minimizing

\[F_{ML}=ln|S| - ln|\Sigma| + trace(S\Sigma^{-1})-p\]

- \(S\): Sample covariance matrix

- \(\Sigma\): Model-implied covariance matrix

- p: Number of indicators

\(\rightarrow\) Perfect fitting model, \(S\) and \(\Sigma\) are identical, so \(F_{ML}\) is 0, as \(S\Sigma^{-1}=I\) and thus \(trace(S\Sigma^{-1})=p\).

Model Fit - \(\chi^2\)

- \(F_{ML}(N-1)\) is approx. \(\chi^2\)-distributed.

- \(\rightarrow\) Significance test, whether discrepancy between \(S\) and \(\Sigma\) is negligible.

- Problems:

- Unreasonable premise

- Needs large enough sample and normal data

- Inflated with very large samples, i.e., oversensitive.

- \(\rightarrow\) Therefore, additional fit indices are considered

Model Fit - Indices

Absolute fit indices, e.g.:

- RMSEA (\(\leq\).05, Hu & Bentler, 1999; but dependent on \(N\), \(df\), and model-specification F. Chen et al., 2008; Kenny et al., 2015)

- SRMR/CRMR (SRMR \(\leq\).08, Hu & Bentler, 1999)

Incremental fit indices, e.g. (reduction in misfit compared to baseline, usually zero covariances):

- TLI (\(\geq\).95, Hu & Bentler, 1999)

- CFI (\(\geq\).95, Hu & Bentler, 1999)

\(\rightarrow\) Report multiple indices (F. Chen et al., 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Moshagen & Auerswald, 2018).

\(\rightarrow\) Don’t overrely on cut-off values (F. Chen et al., 2008; Kenny et al., 2015; Lai & Green, 2016).

\(\rightarrow\) RMSEA and TLI good measures of fit and fitting propensity according to (Bader & Moshagen, 2025), but see also (Bonifay et al., 2025).

Cut-offs…

Practical exoperience has made us feel that a value of the RMSEA of about 0.05 or less would indicate a close fit of the model in relation to the degrees of freedom.

Browne & Cudeck (1993), p.144

In our experience, models with overall fit indices of less than .90 can usually be improved substantially.

Bentler & Bonett (1980), p. 600

\(\rightarrow\) But many simulation studies since (see previous slide).

Model Evaluation

- Global/overall fit

- Local fit

- Interpretability, size, and stat. significance of model parameters

Model Evaluation - Global Fit

- Is the \(\chi^2\)-test significant?

- Are the fit indices within the acceptable range?

- \(\rightarrow\) Can provide conclusive evidence for misfit, but not for good fit of the model.

Model Evaluation - Local Fit I

- Standardized Residual variances:

- \(S-\Sigma\) divided by SEs.

- Interpretable as z-Scores, i.e., absolute values of 2 or 2.58 (for large samples) indicate significant differences on 5% and 1% \(\alpha\)-level.

- Positive values: Model underestimates relationship.

- Negative values: Model overestimates relationship.

- Transform \(S\) and \(\Sigma\) to correlation matrices, then \(\Delta > .1\)? (Kline, 2023)

- Modification Indices (MI): Approx. of decrease in \(\chi^2\) if a spec. parameter is freed.

- Substantial improvement if \(\geq 3.84\) (crit. value of \(\chi^2\) distribution with 1 \(df\))

- Substantive reasons should exist for relaxing constraints.

- Freeing one parameter can affect multiple MIs.

- Problem of overfitting.

Model Evaluation - Local Fit II

- Expected Parameter Change (EPC):

- How large is the change in a parameter if it is freed.

- Given together with MIs.

- Univariate Wald Test:

- Opposite of MI: is model sign. worse if a parameter is fixed to 0.

- If \(< 3.84\).

- This is how the sign. of the parameters are calculated.

- Further ressource on local fit, esp. in the SEM case: Thoemmes et al. (2018)

Model Evaluation - Model Parameters

- Are parameters substantial (i.e., sign. different from 0)?

- No Heywood cases should be present.

- Non-positive-definite matrix indicates problems.

- Estimates should make sense (i.e., sign and size of loadings and correlations).

- Size/variability of standard errors (problems can stem from misspecified model, non-normal data, small N, or other issues).

- Communalities should be substantial.

Interpretation of Parameters

- Unstandardized solution:

- Parameter estimates are based on the original metrics of the indicators and factors.

- Factor loadings are unstandardized regression coefficients.

- Partially standardized solution:

- Indicators are unstandardized and latent variables are standardized or vice versa.

- Completely standardized solution:

- Metrics of both indicators and latent variables are standardized (M = 0, SD = 1).

- Loadings are standardized regression coefficients (between -1 and 1).

Model Evaluation in {lavaan}

- Fit the model with

cfa() - Obtain model fit and parameters with

summary() - Look at (standardized) residuals with

lavResiduals() - Inspect MIs and EPCs with

modindices()

Exercises

Revising the Model

- To improve fit if global/local fit problems or problems in parameters

- Based on MIs/EPCs and substantive reasons \(\rightarrow\) free MIs one-by-one: do the other MIs vanish or stay?

- Note: MIs cannot tell whether to add correlated residuals or add a factor.

- To improve parsimony and interpretability

- Collapsing highly correlated factors

- Higher-order models

More {lavaan} syntax:

# add a cross-loading

model <- '

CF1 =~ MV1 + MV2 + MV3

CF2 =~ MV4 + MV5 + MV6 + MV2

'

# add a cov between residuals of MV3 and MV6

model <- '

CF1 =~ MV1 + MV2 + MV3

CF2 =~ MV4 + MV5 + MV6

MV3 ~~ MV6

'

# constrain or fix parameters

model <- '

CF1 =~ a*MV1 + a*MV2 + a*MV3

CF2 =~ MV4 + MV5 + MV6

CF1 ~~ 0*CF2

'Model comparison

Visualizing the Model

Exercises

“Special” Data

- Non-normal: Robust ML with non-normal continuous data

- Categorical: DWLS with polychoric correlations

- Note: Fit indices may be biased or not interpretable as usual (e.g., Savalei, 2021; Shi & Maydeu-Olivares, 2020; Xia & Yang, 2019) \(\rightarrow\) focus on the Scaled statistics in the

{lavaan}output.

- Note: Fit indices may be biased or not interpretable as usual (e.g., Savalei, 2021; Shi & Maydeu-Olivares, 2020; Xia & Yang, 2019) \(\rightarrow\) focus on the Scaled statistics in the

- Small datasets: Use bounded estimation to avoid convergence issues (see, De Jonckere & Rosseel, 2022)

model <- '

CF1 =~ MV1 + MV2 + MV3

CF2 =~ MV4 + MV5 + MV6

'

# non-normal data:

# robust standard errors and scaled test statistic

fit <- lavaan::cfa(model, data = your_data,

se = "robust", test = "Satorra-Bentler")

# categorical data

fit <- lavaan::cfa(model, data = your_data,

ordered = TRUE)

# small datasets

fit <- lavaan::cfa(model, data = your_data,

bounds = "standard")

summary(fit, fit.measures = TRUE, standardized = TRUE)Missing Data

- Pairwise and listwise deletion: Not efficient and potentially biased

- Simple/single imputation: Underestimates variances and SEs and overestimates correlations

- Instead use:

- Direct ML / FIML: Needs multivariate normal distribution

- Multiple imputation: Random noise is added to regression prediction (needs

{mice}and{lavaan.mi})

model <- '

CF1 =~ MV1 + MV2 + MV3

CF2 =~ MV4 + MV5 + MV6

'

# FIML

fit <- lavaan::cfa(model, data = your_data,

missing = "ml") # or "fiml" or "direct"

# Multiple imputation with {mice} (simplified)

data_imp <- mice(data = your_data %>%

mutate(across(MV1:MV6, ordered)),

method = "polr")

data_imp <- map(seq_len(5),

~complete(data_imp, action = .x, inc = FALSE))

# fit with {lavaan.mi}

fit_imp <- cfa.mi(model, data = data_imp, ordered = TRUE)Exercises

Measurement invariance

- Compare solutions between groups (e.g., gender, language, etc.)

- Levels:

- Configural invariance: Equality of number of factors and pattern of indicator-factor loadings

- Metric invariance / weak factorial invariance: Equality of factor loadings

- Scalar invariance / strong factorial invariance: Equality of indicator intercepts

- Strict factorial invariance: Equality of indicator residuals

- Sequential tests using \(\chi2\)-tests and GOF-measures of constrained and unconstrained models.

- \(\Delta\) Fit indices: see F. F. Chen (2007):

- Loadings invariant if: \(\Delta CFI \leq -.005\) and \(\Delta RMSEA \geq .010\) or \(\Delta SRMR \geq .025\)

- Intercept or residuals invariant if: \(\Delta CFI \leq -.005\) and \(\Delta RMSEA \geq .010\) or \(\Delta SRMR \geq .005\)

- Partial measurement invariance: Only some parameters invariant \(\rightarrow\) free others.

Measurement invariance in {lavaan}

- Fit different models with

cfa()and argumentsgroupandgroup.equalspecified. - Compare using

lavTestLRT() - Compare fit measures (

fitMeasures()) - (

semTools::measEq.syntax()can help generating model syntax)

model <- '

CF1 =~ MV1 + MV2 + MV3

CF2 =~ MV4 + MV5 + MV6

'

# configural invariance

fit_conf <- cfa(model, data = your_data, group = "group_var")

# weak invariance

fit_weak <- cfa(model, data = your_data, group = "group_var",

group.equal = "loadings")

# strong invariance

fit_strong <- cfa(model, data = your_data, group = "group_var",

group.equal = c("intercepts", "loadings"))

# model comparison tests

lavTestLRT(fit_conf, gad7_2f_wfit_weakeak, fit_strong)

# obtain fit measures of interest

fitMeasures(fit_conf)[c("cfi", "rmsea", "srmr")]Exercises

Higher-Order Models

- Capture covariation among factors with a higher order factor \(\rightarrow\) factor correlations are input for second-order factor analysis

- Sequence:

- Fit a first-order CFA solution that fits well

- Examine magnitude and pattern for factor intercorrelations

- Fit second-order factor model, as justified on conceptual and empirical grounds

Exercises

Reporting a CFA (Brown, 2015, p. 129) - I

Model specification:

- Justification for hypothesized model

- Complete description of parameter specifications:

- List indicators per factor.

- How were the CFs scaled (e.g., which MVs were used as indicator variables).

- Describe free, fixed, and constrained parameters.

- Demonstrate that model is identified (e.g., positive \(df\)).

Reporting a CFA (Brown, 2015, p. 129) - II

Input data:

- Sample characteristics, sample size, sampling method.

- Type of data used (e.g., nominal, ordina, interval; scale range of indicators).

- Tests of estimator assumptions (e.g., multivariate normality).

- Missing data and handling thereof (e.g., FIML, multiple imputation).

- Provide sample correlation matrix and indicator SDs (and means if applicable).

Reporting a CFA (Brown, 2015, p. 129) - III

Model estimation:

- Software and version.

- Type of data analyzed (e.g., variance-covariance; polychorric correlations)

- Estimator used (e.g., ML, WLS), as justified by properties of data.

Reporting a CFA (Brown, 2015, p. 129) - IV

Model evaluation:

- Global fit

- \(\chi^2\) with \(df\) and \(p\)

- Multiple fit indices (e.g., RMSEA, TLI), incl. CIs, if appl., and cut-offs used.

- Local fit

- Strategies used for local fit assessment.

- Absence of areas of ill fit or indicate areas of strain in model.

- If model is respecified, provide compelling substantive rationale and document improvement in fit.

- Parameter estimates

- Report all estimates, including nonsign. ones.

- Consider practical and statistical sign. of estimates.

- Include SEs or CIs of parameters.

- If necessary, report steps to verify power and precision of model.

Reporting a CFA (Brown, 2015, p. 129) - V

Substantive conclusions:

- Discuss CFA results regarding their implications.

- Interpret findings in context of study limitations and other considerations (e.g., equivalent models).

Exercises

References

Introduction to Factor Analysis - GSP 2025