fun friends enjoy hurt part commonly chances attracted

fun 1.00 0.66 0.71 0.60 0.62 0.64 0.66 0.70

friends 0.66 1.00 0.73 0.64 0.69 0.73 0.65 0.74

enjoy 0.71 0.73 1.00 0.68 0.73 0.72 0.69 0.72

hurt 0.60 0.64 0.68 1.00 0.64 0.65 0.58 0.64

part 0.62 0.69 0.73 0.64 1.00 0.68 0.67 0.67

commonly 0.64 0.73 0.72 0.65 0.68 1.00 0.64 0.71

chances 0.66 0.65 0.69 0.58 0.67 0.64 1.00 0.67

attracted 0.70 0.74 0.72 0.64 0.67 0.71 0.67 1.00Exploratory Factor Analysis

Institute for Mental and Organisational Health, FHNW

05 June, 2025

Introductory Example: GRiPS

- General Risk Propensity Scale (GRiPS) (Zhang et al., 2019)

- 8 Items assessing domain-general risk taking

- \(\mathbf{\rightarrow}\) Can a single factor, i.e., a single numeric value per person, map the relevant information shared between the 8 items? That is, can we represent the 8d-space by 1d?

Pearson correlations between the 8 items, based on data from Steiner & Frey (2021):

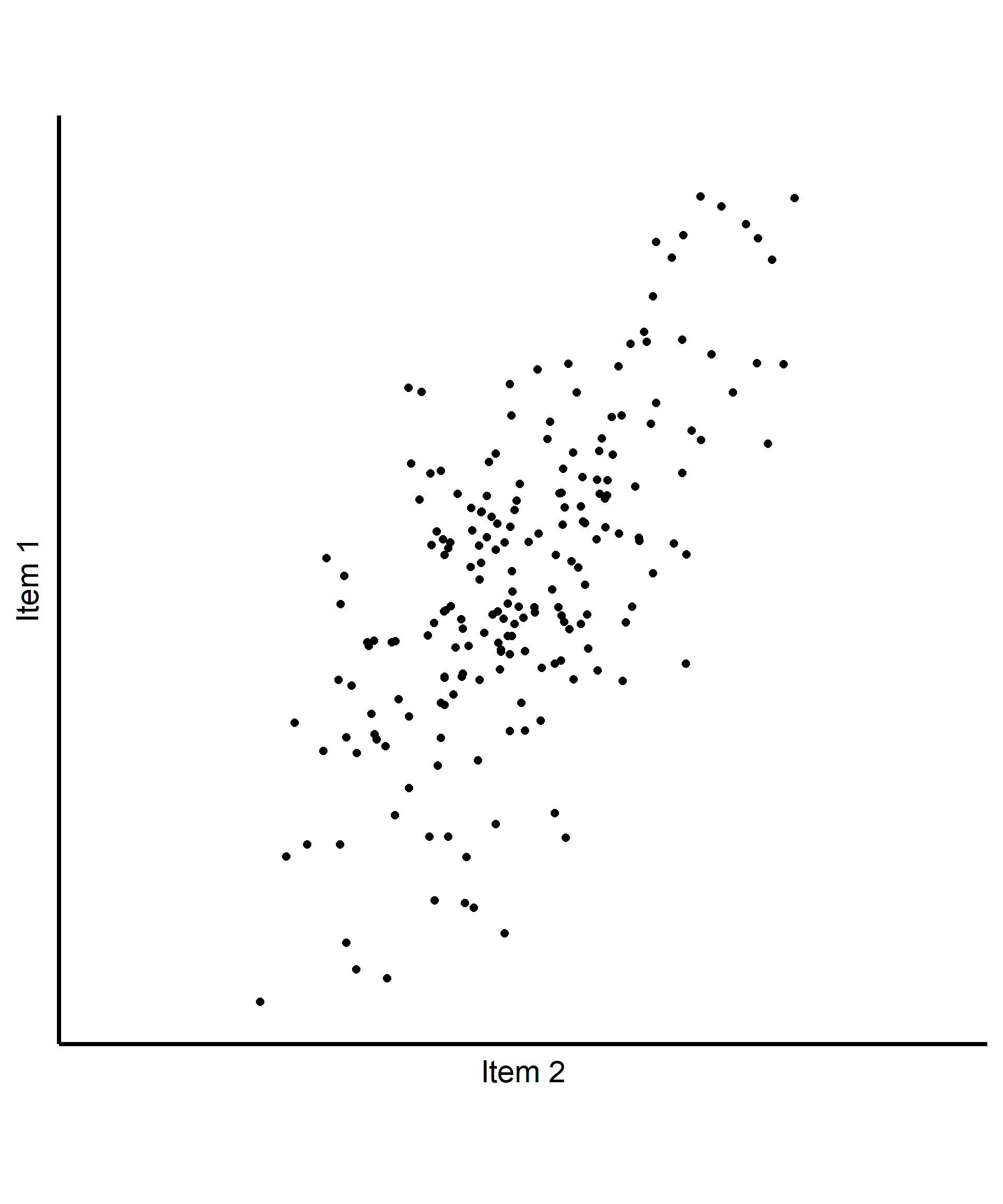

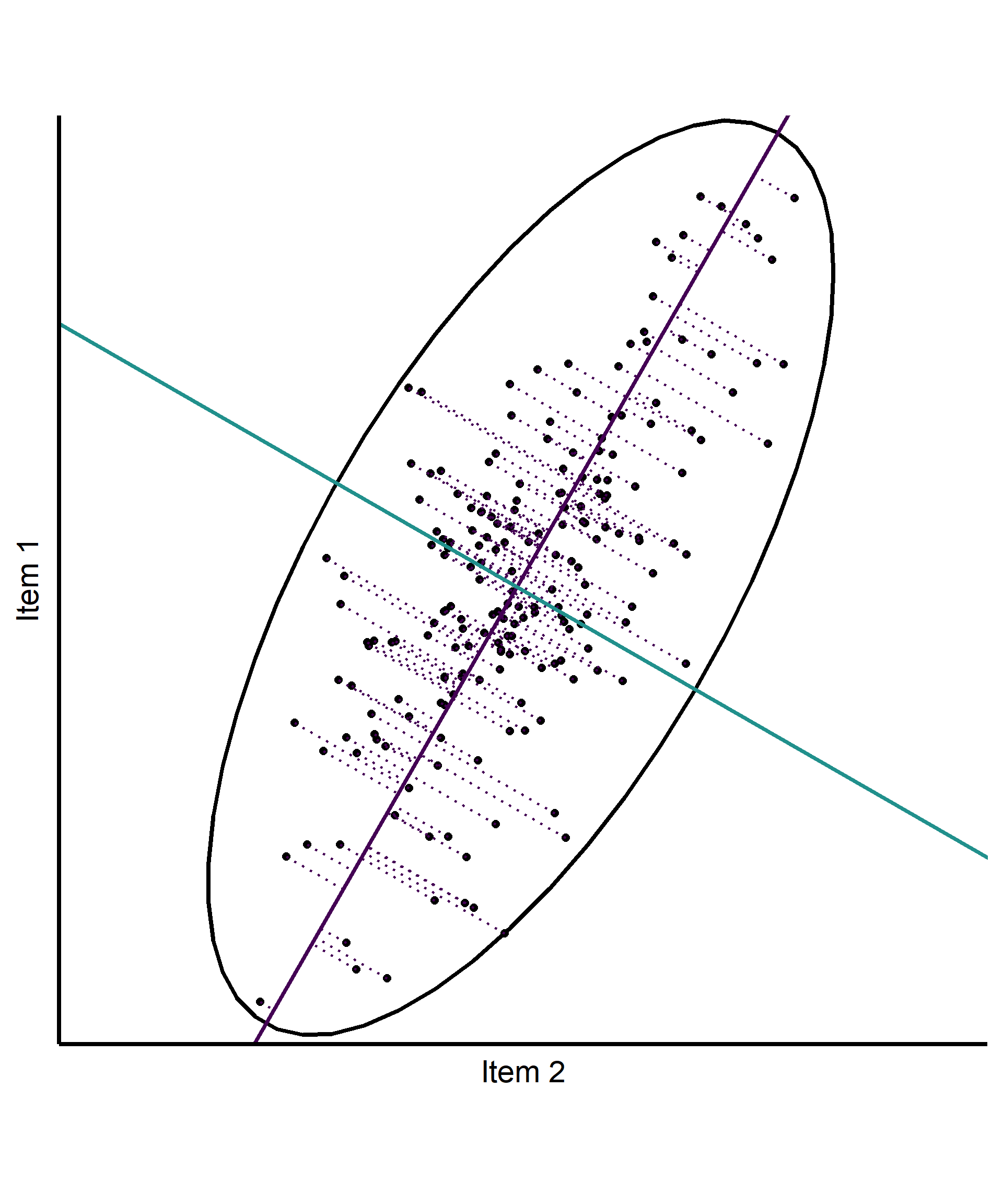

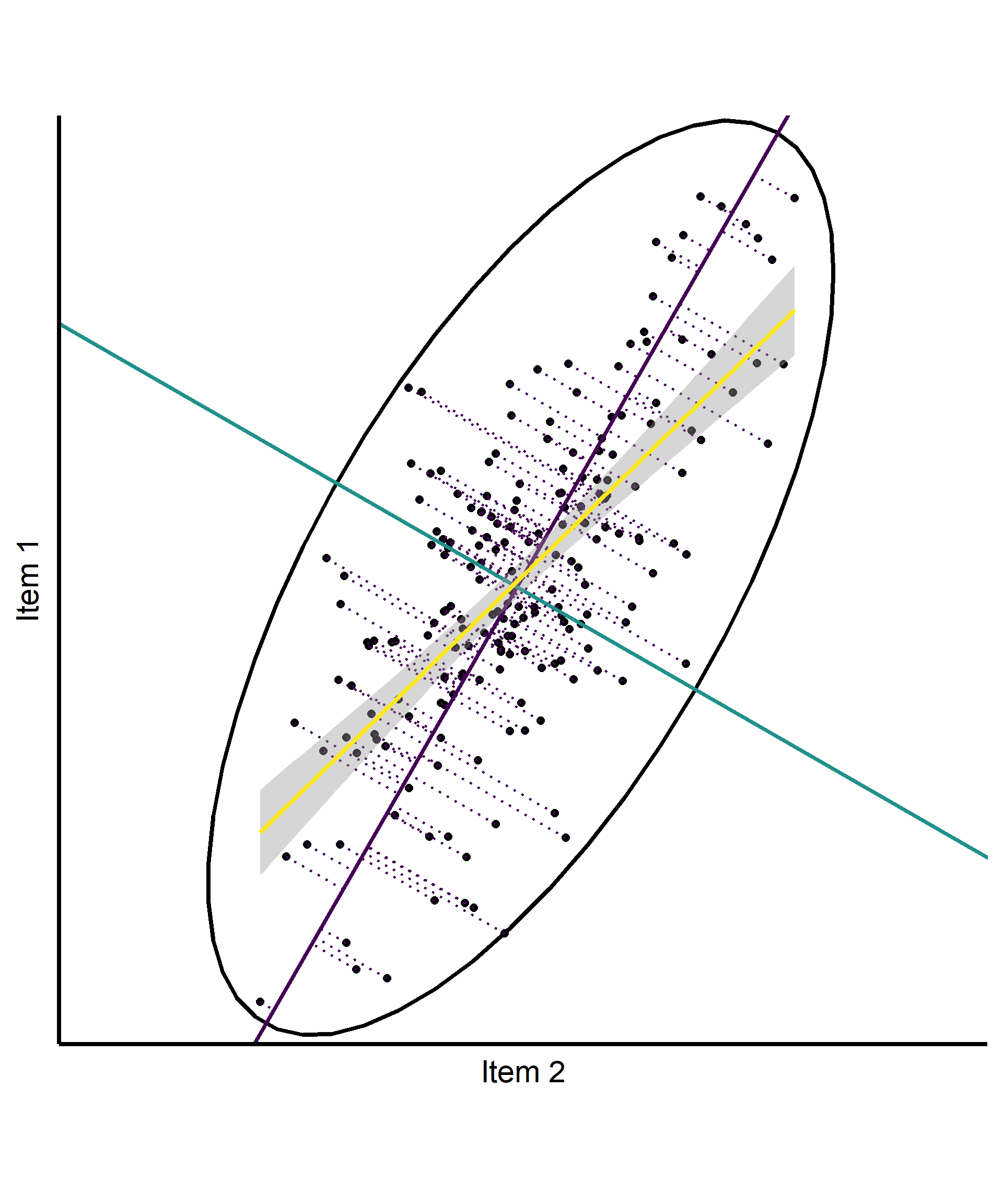

Basic intuition in 2d (based on PCA)

- 2 correlated Items

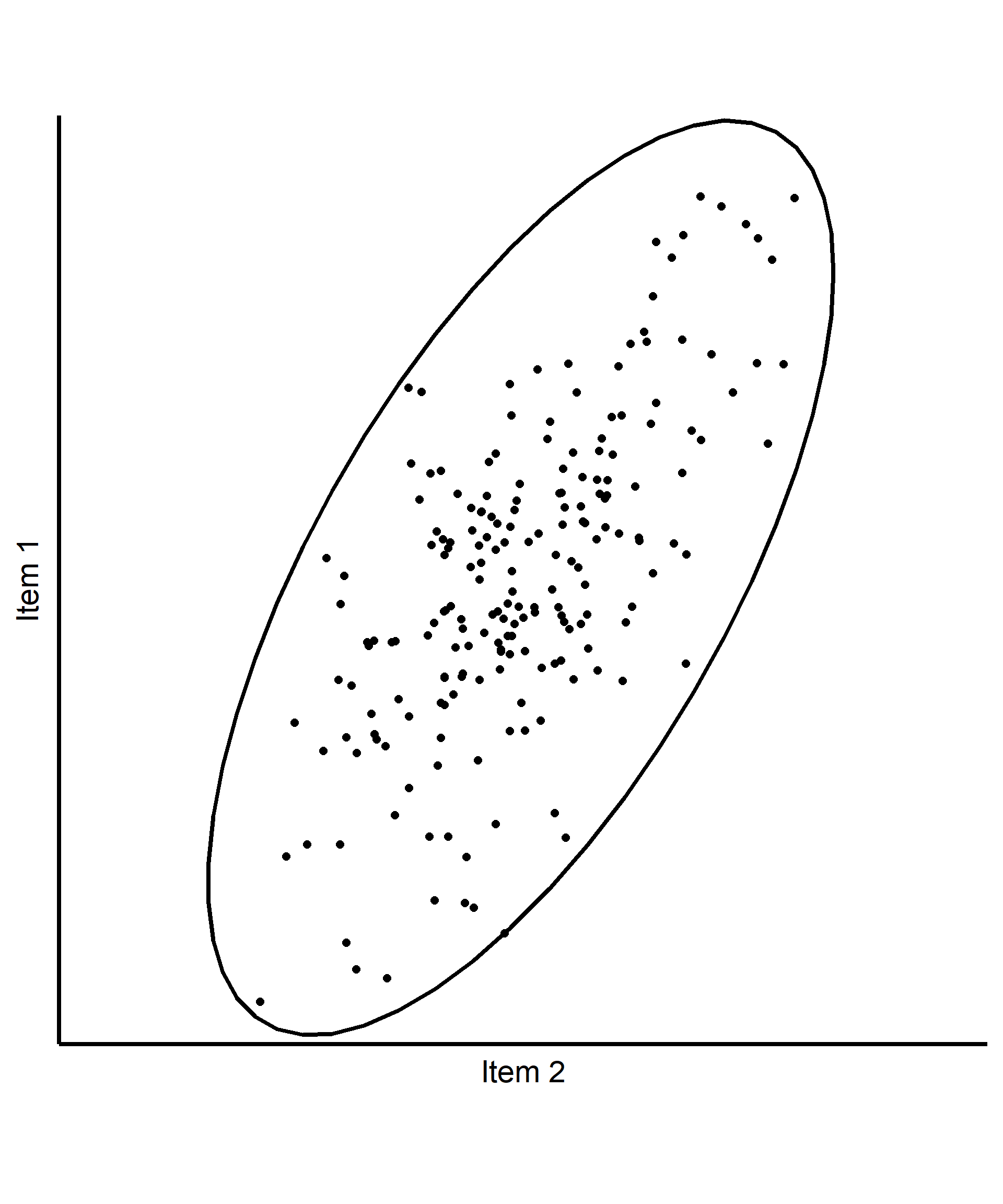

Basic intuition in 2d (based on PCA)

- 2 correlated Items

- Ellipse encapsulating the data based on \(cov(x, y)\)

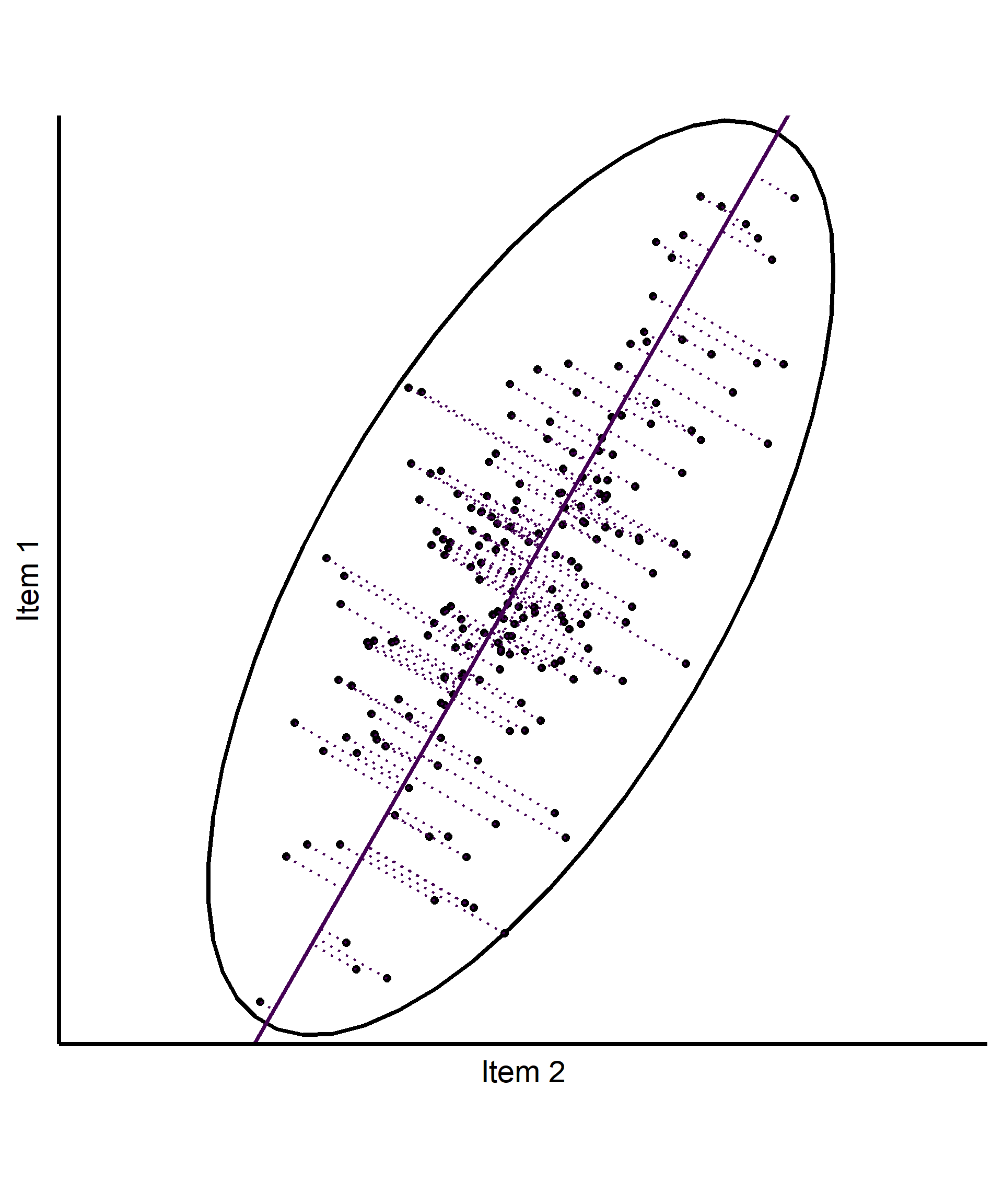

Basic intuition in 2d (based on PCA)

- 2 correlated Items

- Ellipse encapsulating the data based on \(cov(x, y)\)

- Find the axis along which the most variation occurs

Basic intuition in 2d (based on PCA)

- 2 correlated Items

- Ellipse encapsulating the data based on \(cov(x, y)\)

- Find the axis along which the most variation occurs

- Find the axis along which the most residual variation occurs

Basic intuition in 2d (based on PCA)

- 2 correlated Items

- Ellipse encapsulating the data based on \(cov(x, y)\)

- Find the axis along which the most variation occurs

- Find the axis along which the most residual variation occurs

- Note: These axes are different from the regression line

EFA vs. PCA

The first step: Decide between the common factor model and the principal components model

EFA:

- Based on common factor model.

- Account for the structure of correlations.

- Partition variance into common and unique factors.

- Assumes presence of measurement error.

PCA:

- Extract principle components out of MVs, that account for as much variance as possible.

- Create composite scores rather than latent variables.

- No distriction beween common and unique variances.

- Assumes error-free measurement of variables.

\(\rightarrow\) In most cases in psychological science, EFA is more appropriate than PCA, however, PCA is still often used (Fabrigar et al., 1999; Goretzko et al., 2021).

Steps of an EFA

- Calculate the correlation matrix \(R\).

- Test if \(R\) is suitable for EFA.

- Determine number of major common factors.

- Extract common factors.

- Rotate factors to obtain simple structure.

- Evaluate and interpret the model.

Test Suitability for EFA

If major CFs are present, correlations between MVs should be substantial.

- Bartletts test:

Test, if \(R\) is significantly different from \(I\).

ℹ 'x' was not a correlation matrix. Correlations are found from entered raw data.

✔ The Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant at an alpha level of .05.

These data are probably suitable for factor analysis.

𝜒²(28) = 5054.06, p < .001

R was not square, finding R from data$chisq

[1] 5054.06

$p.value

[1] 0

$df

[1] 28Test Suitability for EFA

If major CFs are present, correlations between MVs should be substantial.

- Bartletts test

- Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) criterion:

\[ KMO=\frac{\sum\sum_{k\neq j}r^2_{jk}}{\sum\sum_{k\neq j}r^2_{jk} + \sum\sum_{k\neq j}p^2_{jk}} \]

\(\rightarrow\) Values should exceed .70 (Watkins, 2018) or .80 (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2012).

ℹ 'x' was not a correlation matrix. Correlations are found from entered raw data.

── Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin criterion (KMO) ──────────────────────────────────────────

✔ The overall KMO value for your data is marvellous.

These data are probably suitable for factor analysis.

Overall: 0.955

For each variable:

fun friends enjoy hurt part commonly chances attracted

0.955 0.950 0.947 0.968 0.955 0.958 0.961 0.950

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin factor adequacy

Call: psych::KMO(r = GRiPS_raw)

Overall MSA = 0.96

MSA for each item =

fun friends enjoy hurt part commonly chances attracted

0.96 0.95 0.95 0.97 0.96 0.96 0.96 0.95 Factor Retention Criteria

How many CFs underly the MVs? Many criteria exist (for overviews, see, e.g., Auerswald & Moshagen, 2019; Goretzko, 2025)

- Kaiser-Guttman Criterion:

Compute the eigenvalues of \(R\), take the number of eigenvalues >1. Often used, but don’t use it!

ℹ 'x' was not a correlation matrix. Correlations are found from entered raw data.

Eigenvalues were found using SMC.

── Number of factors suggested by Kaiser-Guttmann criterion ────────────────────

◌ With SMC-determined eigenvalues: 1

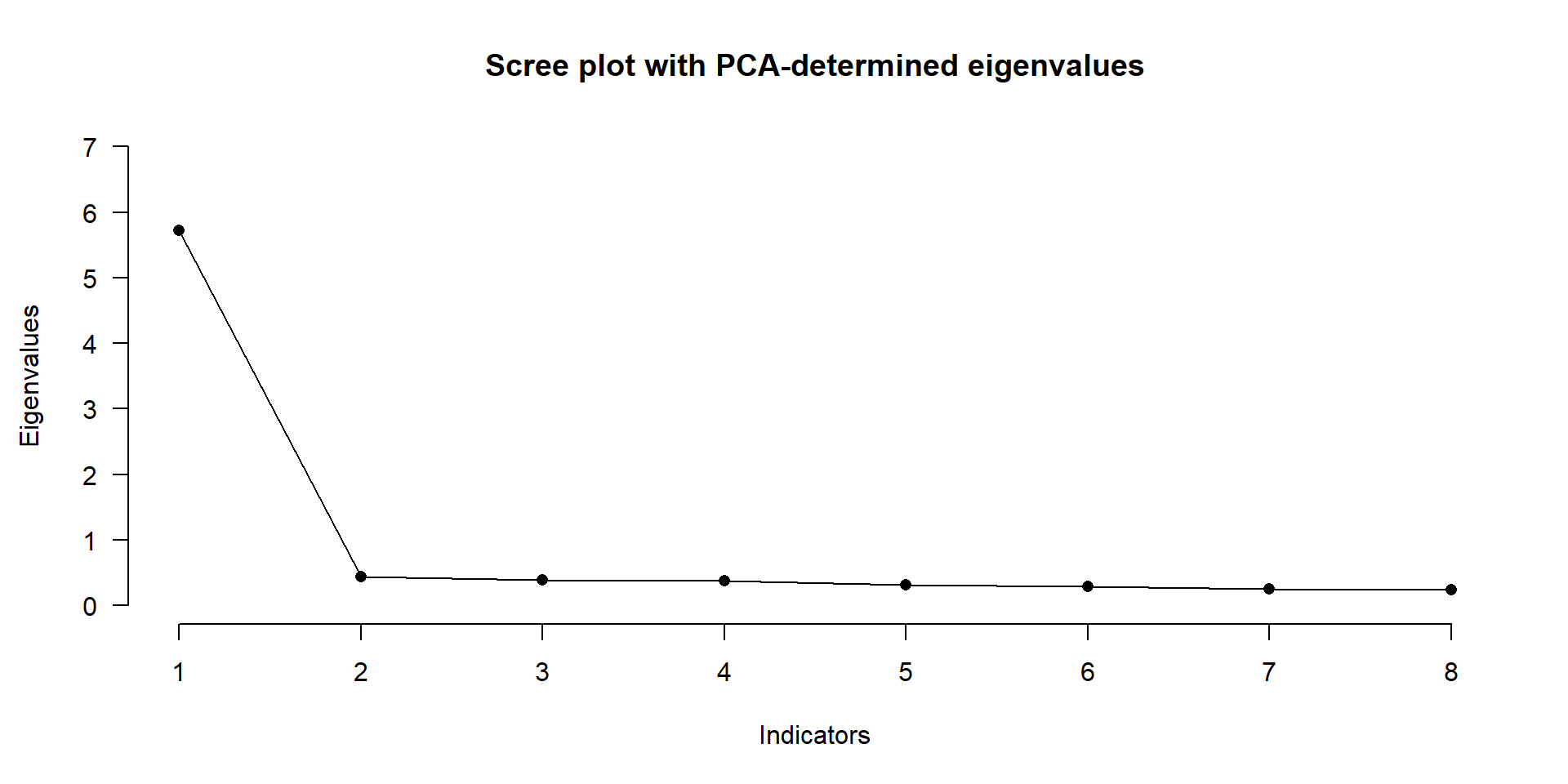

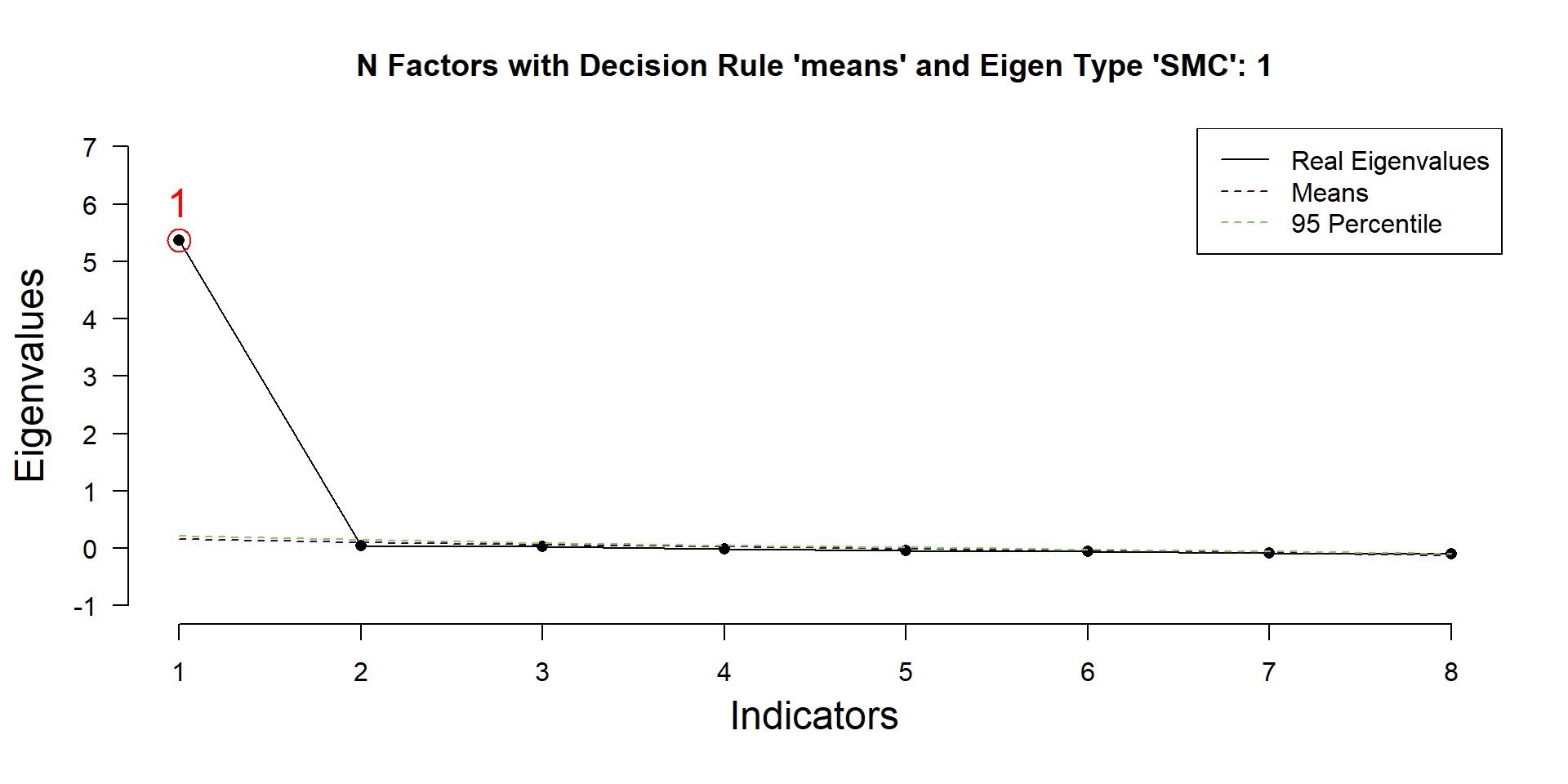

Factor Retention Criteria

Factor Retention Criteria

- Kaiser-Guttman Criterion

- Scree-Plot

- Parallel analysis:

Compare the eigenvalues of \(R\) to average eigenvalues generated from \(b\) random Datasets of same \(N\) as \(R\).

Parallel Analysis performed using 1000 simulated random data sets

Eigenvalues were found using SMC

Decision rule used: means

── Number of factors to retain according to ────────────────────────────────────

◌ SMC-determined eigenvalues: 1

Factor Retention Criteria

- Kaiser-Guttman Criterion

- Scree-Plot

- Parallel analysis

- Many others, e.g. EKC (Braeken & van Assen, 2017), Hull-method (Lorenzo-Seva et al., 2011), Comparison data (Ruscio & Roche, 2012), NEST (Caron, 2025)

Good practice (see Auerswald & Moshagen, 2019): Use multiple criteria, e.g. parallel analysis and comparison data (Goretzko et al., 2021).

EFAtools::N_FACTORS(GRiPS_raw, show_progress = FALSE,

criteria = c("CD", "EKC", "HULL", "PARALLEL","SMT"))

── Tests for the suitability of the data for factor analysis ───────────────────

Bartlett's test of sphericity

✔ The Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant at an alpha level of .05.

These data are probably suitable for factor analysis.

𝜒²(28) = 5054.06, p < .001

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin criterion (KMO)

✔ The overall KMO value for your data is marvellous with 0.955.

These data are probably suitable for factor analysis.

── Number of factors suggested by the different factor retention criteria ──────

◌ Comparison data: 1

◌ Empirical Kaiser criterion: 1

◌ Hull method with CAF: 1

◌ Hull method with CFI: NA

◌ Hull method with RMSEA: NA

◌ Parallel analysis with PCA: 1

◌ Parallel analysis with SMC: 1

◌ Parallel analysis with EFA: 1

◌ Sequential 𝜒² model tests: 3

◌ Lower bound of RMSEA 90% confidence interval: 1

◌ Akaike Information Criterion: 3

Exercises

Factor Extraction

Multiple methods exist. ML and PAF are most popular (e.g., Watkins, 2018):

- PAF

- Non-parametric

- More robust

- ML:

- Assumes multivariate normality

- Less robust

- Can provide fit indices and standard errors

Extract Common Factors – PAF

\[P=\Lambda\Lambda^T+\Theta_\delta, \text{(no }\Phi \text{ as factors are orthogonal)} \]

\[\Downarrow \text{ use } R \text{ as approx. for }P\]

\[R=\Lambda\Lambda^T+\Theta_\delta\]

\[R-\Theta_\delta=\Lambda\Lambda^T\]

\[\Downarrow \text{ use } 1-\textit{SMC} \text{ as approx. for }\Theta_\delta \text{, i.e., } \textit{SMC} \text{ as approx. for } h^2\]

\[R-(1-SMC)=R_r=\Lambda\Lambda^T, \text{ with }R_r \text{ being the } \textit{reduced correlation matrix.}\]

\[\Rightarrow \text{Iteratively obtain } \Lambda \text{ using eigendecomposition of } R_r \text{ until } h^2 \text{ is stable.}\]

Extract Common Factors – ML

When using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation, parameters are found by minimizing

\[F_{ML}=ln|S| - ln|\Sigma| + trace(S\Sigma^{-1})-p\]

- \(S\): Sample covariance (in EFA, usually correlation) matrix

- \(\Sigma\): Model-implied covariance matrix

- p: Number of MVs

\(\rightarrow\) Perfect fitting model, \(S\) and \(\Sigma\) are identical, so \(F_{ML}\) is 0, as \(S\Sigma^{-1}=I\) and thus \(trace(S\Sigma^{-1})=p\).

Model Fit - \(\chi^2\)

- \(F_{ML}(N-1)\) is approx. \(\chi^2\)-distributed.

- \(\rightarrow\) Significance test, whether discrepancy between \(S\) and \(\Sigma\) is negligible.

- Problems:

- Unreasonable premise

- Needs large enough sample and normal data

- Inflated with very large samples, i.e., oversensitive.

- \(\rightarrow\) Therefore, additional fit indices are considered

Model Fit - Indices

Absolute fit indices, e.g.:

- RMSEA (\(\leq\).05, Hu & Bentler, 1999; but dependent on \(N\), \(df\), and model-specification Chen et al., 2008; Kenny et al., 2015)

- SRMR (\(\leq\).08, Hu & Bentler, 1999)

Incremental fit indices, e.g. (reduction in misfit compared to baseline, usually zero covariances):

- TLI (\(\geq\).95, Hu & Bentler, 1999)

- CFI (\(\geq\).95, Hu & Bentler, 1999)

\(\rightarrow\) Report multiple indices (Chen et al., 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Moshagen & Auerswald, 2018).

\(\rightarrow\) Don’t overrely on cut-off values (Chen et al., 2008; Kenny et al., 2015; Lai & Green, 2016).

\(\rightarrow\) RMSEA and TLI good measures of fit and fitting propensity according to (Bader & Moshagen, 2025), but see also (Bonifay et al., 2025).

Exercises

Factor Rotation - Basics

- Unrotated solutions are hard to interpret

- Rotation strives for simple structure:

- Each CF has large loadings for some MVs and small loadings for other MVs.

- Subset of MVs defining CFs should not substantially overlap.

- Each MV should be influenced by only a subset of CFs.

- \(\rightarrow\) Cross-loadings can be ok.

- Two kinds of rotation:

- Orthogonal: Uncorrelated CFs (e.g., Varimax)

- Oblique: Correlated CFs (e.g., Promax, Oblimin) \(\rightarrow\) Preferred!

Factor Rotation - Graphical Intuition

Factor Rotation - Costs of Oblique Rotation

Interpretation of factor loadings differs between orthogonal and oblique rotations:

- Orthogonal rotation: Correlation between CFs and MVs, thus \(R^2=h^2=\lambda^2\).

- Oblique rotation: Two types of loadings

- Structure coefficients (\(\Lambda\Phi\)): Correlation between CFs and MVs, thus \(R^2=\lambda^2\).

- Pattern coefficients (\(\Lambda\): Like standardized, partial regression coeffs: Correlation between CFs and MVs after controlling for the influence of all other CFs. \(\rightarrow\) Can exceed \(|1.00|\).

Exercises

Interpretation

- Goodness of Fit?

- Simple structure present?

- Directions and size of pattern coefficients and factor correlations reasonable?

- Size of communalities (below .4 is low, .4 to .7 is good, .7 or higher is ideal)?

- Heywood cases present (communalities/structure coefficients > 1)?

- Proportion of variance explained?

Interpretation

- Goodness of Fit?

- Simple structure present?

- Directions and size of pattern coefficients and factor correlations reasonable?

- Size of communalities \(h^2\) (below .4 is low, .4 to .7 is good, .7 or higher is ideal)?

- Heywood cases present (communalities/structure coefficients > 1)?

- Proportion of variance explained?

- Large difference between \(R\) and Model-implied \(R\) (\(R_M=\Lambda\Phi\Lambda^T+\Theta_\delta\))?

\(\rightarrow\) Run in R

### Differences between R and R_model:

# EFAtools

fit <- EFAtools::EFA(temp, n_factors = 2,

rotation = "promax")

round(R - fit$model_implied_R, 2)

# psych

fit <- psych::fa(temp, nfactors = 2)

Lambda <- fit$loadings

Phi <- fit$Phi

Theta <- diag(fit$uniquenesses)

R_model <- Lambda %*% Phi %*% t(Lambda) + Theta

round(R - R_model, 2)

# lavaan more complicated -> see solutions in exercisesExercises

Section F - Evaluation and Interpretation in the EFA exercises

Categorical or skewed data

- Skewed / non-normal: Use ML (or WLS) with polychoric correlations (Goretzko et al., 2021) or robust ML.

- With categorical data, use DWLS-estimation and polychoric correlation

- Note: Fit indices may be biased (e.g., Savalei, 2021; Shi & Maydeu-Olivares, 2020; Xia & Yang, 2019) ->

{lavaan}can provide adjusted versions.

# psych option (only WLS, not DWLS):

psych::fa(temp, nfactors = 2, fm = "wls",

cor = "poly", rotate = "oblimin")

### lavaan options

# robust ML with scaled

lavaan::efa(data = temp, nfactors = 2, rotation = "oblimin",

estimator = "MLR")

# polychorric cors with DWLS estimation

lavaan::efa(data = temp, nfactors = 2, rotation = "oblimin",

ordered = TRUE, estimator = "WLSM")Exercises

Recommendations (Goretzko et al., 2021)

- Use 4-5 MVs per factor

- Sample size: at least 300, better 400

- Use polychoric correlations with categorical and non-normal/skewed response data

- Use multiple factor retention criteria

- Use ML-estimation when data allows, otherwise use, e.g., PAF or WLS

- Use oblique rotations

Reporting an EFA (see Watkins, 2018)

- MVs

- Sample size

- Data characteristics

- Software and version

- Appropriateness of data for EFA

- Correlation method

- Factor retention methods and # factors

- Factor model (EFA/PCA)

- Estimation method (ML, PAF, etc.)

- Factor rotation method

- % variance explained by factors (spec. before or after rotation)

- Complete pattern matrix

- Interfactor correlations

- Reliability of factors

- Structure matrix (if different from pattern matrix)

- Eigenvalues for all factors

- Correlation matrix

References

Introduction to Factor Analysis - GSP 2025